April Speaker

Mike McCurdy

Wendy So: A Tale of Two Continents

- Tuesday, April 18, 2023, 7 pm PDT

-

- Meeting ID: 891 8438 9640

Wendy will be speaking on the hunting and eating traditions in two mushroom loving regions: Southwest China, and South Central Africa, and contrast those traditions with ours here in North America.

She has traveled with David Arora chasing mushrooms from California to the Pacific Northwest, Alaska, American Southwest, Europe, Asia, and Africa. She is currently a resident of Mendocino County and was a newsletter editor and speaker coordinator for the MSSF. She now spends her free time experimenting in the kitchen with under-appreciated mushrooms.

President's Message

Natalie Wren Friends,

I hope you have been able to check your spots and explore new territory after these torrential rains. I’ve been getting pretty mixed reports…places that are usually fruiting now are not and places people might not expect fruitings have been surprising.

This last weekend, I was fortunate to have my young niece and nephew visiting from out of state. Both are excellent foragers - they are low to the ground with excellent vision and energy to spare. As a bonus, I had some fresh fungal intel thanks to a friend. We hiked in and found the habitat and conditions were perfect for finding chanterelles. I thought for sure we would strike gold. After much searching, we kept coming up empty. Towards the end of our foray, we ran into another forager who hadn’t been able to find anything for the table, either. We felt super extra lucky with the two chanterelles and one candy cap we eventually found. Yes! We did strike gold!

The very next day, I heard from my tipster friend that a fairly large bounty was found, probably steps from our location the day before. What a great reminder that finding mushrooms really depends on the forager being at the right place at the right time.

Morels are coming soon! It will be interesting to see how the recent snow impacts the fire morel season. Stay tuned!

Natalie

Cultivation Quarters

Ken Litchfield ©April 2017 The Gardener’s Guide to Growing the Garden Giant Mushroom

This month’s Cultivation Quarters is devoted to how to grow the Garden Giant mushroom in your own garden which spawn you may have picked up from the Far West Fungi Farm shop in the SF Embarcadero Ferry Building. You can also obtain the mycelium from Bay Area Applied Mycology at one of their seminars or at the Omni Commons BAAM lab. It is the perfect mulch mushroom for beginners and advanced gardeners to grow in their local back yards, parks, or school gardens for loads of huge edible mushrooms, soil building, and mycoremediation.

Culinary Corner

Hanna Docampo Pham Far West Fungi Santa Cruz Mushroom Store

The first thing you’ll probably notice when you walk in is the brown cardboard boxes full of fresh mushrooms. Like at a farmers market, you can buy the freshest mushrooms 5 days a week from Wednesday through Sundays, 11:00 a.m. to 5 p.m. They offer shiitake, maitake, nameko, king’s trumpet, and lion’s mane, as well as other exotic mushrooms like black trumpet, chanterelles, and truffles when they’re in season. Next to the cash register sits a stack of crisp paper bags for customers interested in buying by the pound. This is the Far West Fungi brick and mortar shop in Santa Cruz!

In the 1970s, John and Toby Garrone started Far West Fungi when the farm nearly closed and the market for fresh mushrooms was just beginning in the U.S. At the time, their farm sold only 3 types of mushrooms. Far West Fungi now sells 52 varieties of mushrooms and keeps all their mushrooms locally grown and certified organic. At their main farm in Moss Landing, they create 20,000 mushroom blocks every week, from a blend of sterilized hardwood mix and bran inoculated with mycelium. The blocks are then incubated, and once the blocks fruit the mushrooms are harvested and go directly to the Far West Fungi’s farmer’s markets and stores, including their shop in Santa Cruz.

If you take a walk down Laurel Street in the heart of Santa Cruz, you’ll easily spot the dark green Far West Fungi store nestled between a line of white buildings. “Everything mushrooms,” is how Ian Garrone, who helps run Far West Fungi with his parents, describes the store. The walls are packed with different products: mushroom tinctures, a collection of dried and powdered mushrooms, and cookbooks, such as the Fantastic Fungi Community Cookbook and The Mushroom Hunters Kitchen. In mini refrigerators are packaged house made goods, like frozen mushroom soup and both candycap and huckleberry cheesecake. For anyone seeking a gift for a mushroom hunter, you’ve come to the perfect place! There are cards, mugs, tea towels, posters, shirts and hoodies, all mushroom themed of course. If you’re interested in growing your own mushrooms, liquid culture syringes and spawn plugs for sale. You can even find mushroom blocks for sale, mushroom home growing kits that replicate the same process as used at Far West Fungi farms.

The food I tried from the Far West Fungi’s Santa Cruz Store!

The food I tried from the Far West Fungi’s Santa Cruz Store!

The best part: the mushroom themed cafe! It features a menu inspired by street food at fungi festivals and fairs that changes seasonally. I recently tried all of the savory vegetarian dishes offered on their spring menu. Most of the dishes are vegan or vegetarian, like the moco loco with a layer of white rice, green onions, and porcini gravy with a rich, veggy-filled patty instead of the traditional beef patty, or the muffaletta, a hoagie roll with mozzarella, provolone, pickled olives and vegetables, “mortadella” (king trumpet), “capicola” (marinated portabella), and “salami” (maitake), a meatless sandwich.

The cafe serves an Italian arancini, which are risotto balls stuffed with mozzarella cheese and porcini that are rolled in breadcrumbs and deep fried, then served with a chili pepper and mushroom marinara sauce. The zuppa soup is another Italian dish they offer, made of fresh rainbow chard, carrots, onions in a creamy broth with “meatballs” (king trumpet and crimini), which creates a delicious vegan soup. The soup is best paired with the truffle grilled cheese, that is just like it sounds: a sandwich of black truffle tapenade, bluefoot mushroom butter, melted gruyere and swiss cheese that’s grilled to perfection in a panini press. I also tried the el porteno empanadas. El porteno translates to “person from the port”, referring to the people of Buenos Aires, a famous port city in Argentina. The empanadas are made from an Argentinian style buttered pastry folded by hand and filled with tree oyster, king trumpet, crimini, shallots, and aged parmesan, then baked until crispy.

My favorite dish though was the chanterelle rustico. In Southern Italy, Calabria is known for their “N’duja sausage”, a cured, spreadable pork sausage that is flavored with local peppers. The chanterelle rustico is a puff pastry filled with spicy, Calabrian-style chanterelle “sausage”, king trumpets, and grilled corn. The texture of the chanterelles was a lot softer than if they were just fried, but this made a delicious, savory paste for the pastry that I loved. For dessert, I had a candy cap cookie, which encapsulated the sweet maple flavor of candy caps excellently and is truly the best candy cap dessert I’ve tried. While you can visit the Far West Fungi store in San Francisco, I recommend checking out the Santa Cruz location for their marvelous one-of-a-kind mushroom cafe.

This month’s recipe is king trumpet empanadas, which I made using king trumpets from Far West Fungi.

King Trumpet Empanadas

By Hanna Docampo Pham

Makes 16 empanadasDough

4 cups all purpose flour*

1 tsp salt

½ cup butter

4 egg yolks

1 cup water

*I used whole wheat flour when I cooked the empanadas, but all-purpose flour works far better because the dough will be fluffier and less grainy

Filling

500 grams king trumpet mushrooms

3 garlic cloves

Olive oil

1 large onion

1 bunch of green onions

Mozzarella cheese

Salt & pepper to taste

1 egg

To make the dough, begin by mixing the flour and salt in a large bowl with a wooden spoon. Once the mixture is combined, melt the butter. Add the melted butter, egg yolks, and water to the bowl and mix it together until a dough starts to form.

On a flour dusted surface, knead the dough for at least 5 minutes. If the dough sticks to your hands, add a little more flour at a time and continue to knead the dough until the consistency is right.

Cover the dough with plastic wrap or a towel, and let it rest in the fridge for at least 30 minutes.

The king trumpets from Far West Fungi, before and after being chopped

The king trumpets from Far West Fungi, before and after being chopped

For the filling, trim the mushrooms and slice them into small, bite sized pieces. Depending on how you slice the mushrooms, you may have a thicker or thinner filling. Cut the onion into 4 pieces, then slice it. Slice the green onions. Set aside the onions and green onions for later.

Peel and mince the garlic. Heat a pan to medium high and coat it with olive oil. Sauté the garlic for one minute, then add the mushrooms. Cook the mushrooms until they are fully cooked, stirring the mushrooms occasionally so they don’t burn. If the mushrooms start to stick to the pan, add a little more oil.

Once the mushrooms are fully cooked, add a little more oil to the pan and add the onions. Sauté the onions and the mushrooms for 5 more minutes, then add the green onions. Cook until most of the onions are caramelized. Add salt and pepper to taste.

Preheat the oven to 450º F. On a clean, lightly dusted surface divide the dough into 16 pieces. Roll each piece of dough into a ball, then roll out the dough into a disk with a rolling pin. The dough should be thin and nearly the size of a small plate.

Fill a bowl with water, and slightly wet the edges of the dough. Add about 1 ½ tablespoons of filling to each empanada (or until full), and then top with a piece of mozzarella cheese. Seal the empanadas by folding them in half, then crimp the edges of the empanada with a fork.

Place the empanadas on a baking sheet lined with parchment paper. Prick the top of the empanadas with a fork, to avoid them from bursting in the oven.

Beat an egg in a small bowl and brush the empanadas with the egg wash. Bake the empanadas for 15 to 20 minutes, or until they are golden brown. Enjoy!

Culinary Group

The MSSF Culinary Group is a participatory cooking group open to all MSSF members who are interested in the gastronomical aspects of mushrooming.

Gatherings are generally held on the first Monday of each month at 7:00 p.m. at the San Francisco County Fair Building, "Hall of Flowers" in Golden Gate Park; - at 9th and Lincoln. Members of MSSF and the Culinary Group, and their guests, are invited to attend.

Any MSSF member may register to attend a Culinary Group dinner in the "Members Only" area of the Society's website, www.mssf.org.

( Covid protocol: please do not register or attend if you are not fully vaccinated for Covid 19, or if you are feeling unwell or experiencing any covid or cold symptom).

OYSTER MUSHROOM FUNGUS USES NERVE GAS TO PARALYZE AND EAT TINY WORMS

By Alice Klein www.newscientist.com, 18 Jan, 2023

Oyster mushrooms are delicious, but they have a little-known dark side: the fungus that produces them paralyses and kills nematode worms using a nerve gas, before sucking out their insides.

Oyster mushrooms are the reproductive structures — or fruiting bodies — of the fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. We have known since the 1980s that this fungus preys on nematodes, which are microscopic roundworms, but how it does this has been a mystery.

Yen-Ping Hsueh at Academia Sinica, a research institute in Taiwan, and her colleagues previously discovered that P. ostreatus contains tiny, lollipop-shaped structures that break open when nematodes press their heads against them. They have now found that, once ruptured, these structures release a gas that is highly toxic to nematodes’ nervous systems.

The researchers determined this by first inducing thousands of random genetic mutations in the fungus, after which they noticed that mutants lacking these lollipop structures were no longer toxic to the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.

Next, the researchers analyzed the contents of the lollipop structures in non-mutant fungi and found that they were packed with a volatile chemical called 3-octanone. When they exposed four different nematode species to this chemical, it triggered a massive influx of calcium ions into nerve and muscle cells throughout their bodies, leading to rapid paralysis and death.

Hsueh calls this a “nerve gas in a lollipop” killing strategy. The toxic lollipop structures are present on hyphae, the long, branching structures that grow inside rotting wood and make up most of the fungus. The oyster mushrooms themselves are non-toxic, says Hsueh.

After the fungus kills its prey, its hyphae grow into the nematodes’ bodies to suck out their contents. It may do this to absorb nitrogen, since this nutrient is deficient in the rotting wood on which the fungus mostly grows, says Hsueh.

Nematodes are the most abundant animals in soil, which makes them a natural food choice for fungi, she says. Other fungi use different tactics to catch nematode prey, including sticky traps and nooses that tighten around their necks.

The finding that P. ostreatus feeds on nematodes has led to some discussion in the vegan community about whether oyster mushrooms are a truly vegan food.

Journal reference: Science Advances, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ade4809

Notes from the Underground

(Repost: The Pioneer Valley Mycological Association) The Mysterious World of Mycelium

By Jonathan Kranz

Open any mycology book, attend any introductory fungal lecture, and among the first lessons comes the understanding that the mushrooms we seek are merely the fruiting bodies of the fungi we can’t see: the metabolism of this creature, its day-to-day living, growing, eating, exploring, and ultimately, dying, are fulfilled invisibly within a thready, cobwebby network of hyphae called, “mycelium.”

Fungi thrive in the underworld, hidden within the dark recesses of plant tissues, dead or dying wood, and that simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary substance, soil. Most of the time, we mushroom hunters see nothing of this life beyond the few threads that cling to the base of freshly harvested specimens, or an ivory mycelium spread thin, damp, and lacy on the underside of a freshly turned log. Fungi thrive in the underworld, hidden within the dark recesses of plant tissues, dead or dying wood, and that simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary substance, soil. Most of the time, we mushroom hunters see nothing of this life beyond the few threads that cling to the base of freshly harvested specimens, or an ivory mycelium spread thin, damp, and lacy on the underside of a freshly turned log.

We know that fungi, like animals, are heterotrophs that must consume other life in order to live. But unlike animals that ingest food and excrete waste, fungi live “inside-out,” excreting the chemistry necessary to liberate nutrients they can then absorb. With so much activity outside itself, where does its body end and the environment begin?

How do we imagine such a porous, ambiguous creature? What would be its shape, its texture and form? If we had a superpower that would allow us to picture the mycelium distinct from its context, what would we see? Would it resemble clouds or pillows, neural networks or explosive nebula? Does each individual (and what does individuality mean for a being so widely spread out?) maintain its own distinct turf with discrete boundaries, or can the hyphae of many individuals intertwine, creating a three-dimensional tapestry of multiple species underground?

“We don’t know exactly what’s going on below ground.”

According to David Hibbett, PhD, Professor of Biology at Clark University, and a good friend of both the PVMA and BMC, “different fungi have different forms.” The saprobes that feed on dead wood – the brown and white rotters -- for example, are “more homogenous than the soil [dwellers].” These will indeed defend distinct territories often defined by the spalting favored by woodworkers. [Image Source]

“But the three-dimensional [spread] of ectomycorrhizal mycelia?” says Hibbett. “We don’t know.”

That large “not-knowing” became the underlying theme of my pursuit of the underworld. Serita Frey, PhD, Professor of Natural Resources, and the Environment at the University of New Hampshire, concurs: “We simply don’t  know what’s going on below ground.” In a time when the recently deployed James Webb Space Telescope seems to be producing near daily insights into galactic systems millions of light years away, we have significantly less understanding of the natural dynamics of soil systems literally under our feet. The reasons why are not obscure: it’s dark down there and the complex interrelationships of so many organic and inorganic variables are difficult if not impossible to recreate in the lab. [Image Source] know what’s going on below ground.” In a time when the recently deployed James Webb Space Telescope seems to be producing near daily insights into galactic systems millions of light years away, we have significantly less understanding of the natural dynamics of soil systems literally under our feet. The reasons why are not obscure: it’s dark down there and the complex interrelationships of so many organic and inorganic variables are difficult if not impossible to recreate in the lab. [Image Source]

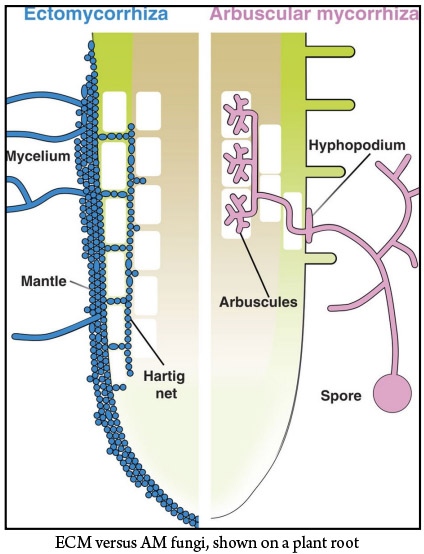

Here's what we do know. First, among the fungi that live symbiotically with plants, we must distinguish the endomycorrhizal arbuscular fungi (AM) that associate with 85% of all plant species from the ectomycorrhizal fungi (ECM) that associate with merely 5% of terrestrial plants, including many of our familiar forest trees: oaks, birches, pine (but not, sadly, maples). The hyphae of the former, AM fungi actually penetrate into the root cells themselves, creating arbuscules – branched, tree-like organs -- for the exchange of nutrients/water for life-giving sugars. AM fungus activity is essential for life on Earth, but their mycelia do not create mushroom fruiting bodies.

The ectomycorrhizal fungi are less prevalent, but more significant to us mushroom hunters because of the bounty they create on the forest floor. Underground, their hyphae do not penetrate plant cell walls, but do create a Hartig net between the epidermis and cortex to facilitate exchanges.

An examination of tree rootlets, even with relatively minor magnification, will reveal a hyphal “wrapping” that bonds plant and fungus together. reveal a hyphal “wrapping” that bonds plant and fungus together.

In either form, AM or ECM, the mycelia extend beyond their symbiotic root foundations to explore for water and nutrients they can exchange for carbohydrates. According to Dr. Frey, the reach of this hyphal extension is “not well documented and depends on the species and growth habit, with some hyphae extending a significant distance from colonized roots.”

Yet, oddly enough, despite the overwhelming number of plant/fungi relationships and the oft quoted statistic of 1–40 miles of hyphae per teaspoon of soil, “only 1% to 2% of soil surface area is occupied by microbes,” says Dr. Frey, “leaving lots of room for mycelia to explore without bumping into each other.”

Mycelia may not be colliding, but the soil environment remains profoundly crowded. Dr. Frey estimates that some two – three thousand different fungal species, active and resting (i.e., spores, sclerotia), can inhabit that same teaspoon of soil. That’s why, Dr. Hibbett suggests, biologists are exploring “metagenomics,” “metatranscriptomics” and “metaproteomics” (DNA > RNA > proteins ) to find “clues to the physiological potentialities of an environment beyond the genome of any one organism.”

If the ultimate nature and form of mycelia remains frustratingly inconclusive, we can take comfort in knowing that its activity – like the search for quantum gravity or the nature of black holes – is as mysterious to our best scientists as it is for us lay mushroom enthusiasts. We end where we began, but perhaps with more humility and awe; for every mushroom we pick and study, there is a secret world of mycelium that, like the dreams in our heads and the stars in the sky, reward us with an even greater capacity for wonder.

|