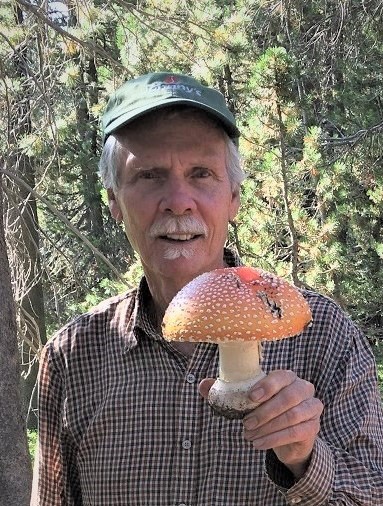

November Speaker

Mike McCurdy Medicinal Mushrooms

Mushroom Medicine: Latest News, Controversies, and Uses

Join Dr. Christopher Hobbs, author of the ground-breaking book Medicinal Mushrooms (first edition, 1989), for a lively discussion on all things fungal and healthy!

Tuesday, November 21st, 2023 at the Randall Museum.

Doors open at 6pm - Hospitality hour and ID of mushroom specimens. General meeting and Zoom session start at 7pm.

Join the Zoom Meeting

Meeting ID: 891 8438 9640

Passcode: 608192

A thorough and practical review of the science and traditional use of the most widely researched medicinal mushrooms (especially turkey tails, shiitake, cordyceps, maitake, and chaga), based on many years of on-going clinical practice will be presented. Focus on lesser-known constituents and benefits--ergothioneine, chitin, and phenolics.

Learn about their current use in modern integrative health care, and in the kitchen as one of the healthiest and most nutritional foods you can eat! Christopher will share some of his favorite recipes and some great traditional recipes for a variety of fungi.

Learn how to make mushroom extracts at home for clinical and personal use to maximize healing and nutritional benefits.

Dr. Christopher Hobbs is a fourth generation, internationally known herbalist and mycologist, licensed acupuncturist, herbal clinician, research scientist, consultant to the dietary supplement industry, expert witness, botanist, public speaker, and author of over 20 books and numerous articles with over 40 years of experience. He is the author of the recent book “Christopher Hobbs’s Medicinal Mushrooms, the Essential Guide,” with German and English editions.

He earned his Ph.D. at UC Berkeley with research and publication in evolutionary biology, biogeography, phylogenetics, the chemistry of plants and fungi, and ethnobotany. Now faculty at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Cultivation Quarters

Ken Litchfield (repost from November 2014) November tends to be the usual start of the rainy season in northern California. It seems that the fungi living in the dead heartwood of trees require less rain to activate from the long summer drought than some of the mycorrhizal species that need repeated rains for the soil to be saturated around the tree roots. This month and next, we’ll traditionally see fruitings from wood eaters, stump feeders, and tree trunk hollowers that feed on the dead heartwood of trees.

Oysters ( Pleurotus ostreatus) and lion’s mane ( Hericeum erinaceus) are two edibles that most folks can find on decaying hardwoods. Lion’s Manes are often perennial in the same oak hollow year after year, while oysters will bloom all over downed or decrepit hardwoods until they totally rot away. Also fruiting early are the poisonous stump feeders used for dyes: the sulfur tuft ( Hypholoma fasciculare), Jack O’Lantern ( Omphalotus olivascens), and the big gyms ( Gymnopilus ventricosus). These can be collected in their prime and dried for dyeing fabric art. The big gyms are poisonous in the sense that they have some “toxic” non-felonious psychoactive components that put them in demand … not just for the dye.

Jack o’ Lantern growing on Oak

One method of cultivating these wood lovers is to collect the mushrooms’ tight tough bases after harvesting the tender ones, and then stuff the bases into the cracks of fresh stumps or wood chip piles of their favorite trees. These trees often have snags that can be broken or cut off the main branch or trunk that is fruiting, and transplanted, with their internal fungus, among fresher logs, trunk hollows, or wood chip piles in your garden patch or a woodland nearer to you. This is a simple method of inoculating fresher logs or tree trunks with the mycelial spawn inside the branches, or from the spores of the mushrooms as they fruit out of the branch.

These mushrooms can also be made into inoculating slurries. Grind fresh or past prime fruiting bodies in a blender of water and pour over the cracks of downed logs or wood chip piles. The fungi can then start digesting the wood from the spores and cloned mycelium in the slurry.

One of the most common ways to inoculate logs or tree trunks with mushrooms is to “plug” the wood with commercial wooden carpentry dowels inoculated with a number of different kinds of mushroom spawn. With some canning skills, you can also make your own spawn dowels in a pressure cooker in your own kitchen. The dowels act like seeds or bulbs of plants that will grow into the heartwood of logs from the mycelium feeding in the wood of the dowels. With a drill bit slightly larger than the diameter of the dowel, drill holes into the log at intervals in which to push the dowels with a screwdriver. If the logs are very dry, they may require soaking overnight or squirting water into the holes before plugging the dowels. Logs are usually human carrying size of 4” to 24” in diameter and 1” to 4” long.

You may have heard that you should drill 1” holes for 1” dowels all over the surface and ends of the log before covering the end of the exposed dowel with melted paraffin to keep it from drying out while sprouting in the log. However, a better way to plug the log is to drill deeper holes (from 4” to 8” deep) with long drill bits, almost passing through the entire log. This way, the last of several dowels tapped into the hole works as a plug that keeps it from drying out. Aside from not wasting paraffin, the real advantage to this method is that it more closely simulates what may happen in the wild when a branch breaks off a tree, exposing the heartwood to infiltration by a fungus.

The outside few inches of a typical tree trunk or large branch are newer living tissues that surround the older dead heartwood in the center of the tree. This outside living cylinder, however, contains juicy antifungal properties that ward of infections to the tree. This is why one should avoid plugging freshly cut logs until a couple of months after cutting; it allows much of the antifungal volatile components to evaporate. But no wait is needed when plugging deep into the heartwood.

You can see sappy droplets of these components when you cut down any living tree; a sappy conifer is an especially good example. The outside living rings of the cross section exude droplets of sap, whereas the drier inner core is typically where the saprobic fungus lives and eats and hollows out the tree. It doesn’t bother the living tissue and can completely hollow out a large tree without killing it. This may affect the integrity of the tree in a forest by offering less support by the central heartwood, but the tree can compensate by reinforcing the living cylinder to support itself.

These hollow trees can be homes for birds or beehives. The moisture given off by the birds’ respiration as well as the nectar evaporation needed to make honey for bees actually works symbiotically with the fungus, providing more moisture for the fungus and larger hollows for nests and hives.

Becoming Unlost In The Woods

Wren Hudgins Last week I went foraging with some friends. And for the first time ever, I got really lost. Right after we got back to the homestead, my good buddy said “oh yah, I wanted to bring that article from last month’s Fungi magazine about how not to get lost in the woods, but I’ll get it to you later. They said the first thing to do when you think you’re lost, is just stay put.” MmmHmm, timing is everything~!~

(repost from the Bulletin of the Puget Sound Mycological Society June 2015)

The story goes that Daniel Boone was once asked if he had ever been lost in the woods. His oft quoted response was some variation on “Well, there was a week or two where I was pretty confused as to where I was, but I’ve never been lost.” Beyond the amusement, the story illustrates two important points:

• Being lost is a state of mind, almost a decision one makes. Boone didn’t decide he was lost despite a week or two of wandering.

• The panic that often accompanies the state of being lost is optional.

This article will summarize research on the behavior of lost persons, discuss strategies potentially useful in the event one is already lost, and, finally, discuss prevention strategies. The research on lost-person behavior has been expertly summarized by Robert Koester in his 2008 book Lost Person Behavior; a Search and Rescue Guide for Where to Look for Land, Air and Water. Material from his book is used here with the author’s permission. Information on obtaining his book is at the end of this article.

Being lost is a special case and a subset of being missing, which includes such circumstances as being stranded, overdue, trapped, incapacitated, and others. It’s an important distinction because lost persons act differently from those who are missing for other reasons. So, for this article we focus only on the lost. A reasonable definition of “lost” comes from Ken Hill, as quoted in Koester’s book, as having two components:

• confusion as to current location in respect to finding other locations

• inability to reorient.

General Tendencies of Lost People

Search and rescue literature has come a long way and is much more statistically based than ever before. We know some general tendencies of lost-person behavior and we know more detailed tendencies of specific groups. Mushroomers fall into the “gatherer” category which would include anyone out in the woods collecting anything. In Koester’s database, mushroomers make up 70% of the “gatherer” category. However, first we’ll cover ten general tendencies of most lost persons.

1. The lost are not randomly distributed over the landscape, but cluster in somewhat predictable locations.

2. There is some evidence that solo lost persons fare worse than a group of lost persons and that solo males fare worse than both lost groups and lost solo females.

3. Lost combinations of an adult and a child tend not to wander very far.

4. The median length of a search is 3 hours and 10 minutes (median is the middle point, the 50th search out of 100).

5. The mean (average) length of a search is 16 hours and 20 minutes. (This is skewed by a few exceptionally long searches, so “median” may be a better measure of the central tendency.)

6. When lost without landmarks, people do tend to walk in circles; 55% veer to the right and 45% veer to the left.

7. When given a choice of paths in unknown woods, people make the following choices about turning.

• 69% of right handed people who drive on the right side of the road, go right,

• 47% of right handed people who drive on the left side, go left, and

• 70% of left handed people, no matter what side they drive on, turn left.

8. There is a tendency for both rescuers and lost persons alike to veer away from irritants like wind, steep slopes, and tight vegetation.

9. There is moderate evidence that lost persons tend to walk downhill more than uphill.

10. There is considerable evidence that lost persons walk much more during the day than during the night.

Knowing these tendencies gives you a chance to correct them. For example, if you are trying to contour around a slope and remain at the same elevation, you will know that over some distance, there is a tendency to drift downhill. You can then take steps to attend to that variable and stay level.

Reorientation Strategies

So, generally speaking, the following are the strategies lost persons tend to use to reorient themselves. I will list these in order of descending efficacy (in my opinion). Please bear in mind that a number of variables affect whether a particular strategy is a good one at any given time. My ordering is a general one, and suggestive, intended to provoke thinking.

1. Use travel aids (compass, GPS, landmarks, cell phone with GPS application).

2. Backtrack (only if you can do this carefully and actually recognize the ground you are covering as familiar, which, in turn, depends on being observant on the way in).

3. Stay put.

4. Enhance your view. Climb to a higher place to see the “big picture” and possibly get cell phone reception.

5. Sample different routes. Note where you are and follow paths in different directions to see if anything looks familiar, but keep the original place in sight; then return to the original place, sample a different path, etc.

6. Sample different directions. Same as above but in the absence of paths, sample east, west, north, and south.

7. Travel a route. Pick a path and keep following it.

8. Travel in a direction. Pick a direction and keep traveling in that direction.

9. Use folk wisdom. Follow such adages as “all streams lead to civilization” or “moss only grows on the north side of trees.”

10. Travel randomly. This is often accompanied by panic and follows the path of least resistance.

11. Do nothing to help yourself. Don’t travel, put on rain gear, or warm clothes, build a fire, anything.

Mushroomers’ Special Risks

We mushroomers, however, present special risks because of a number of factors. The science, and it is a science, of finding lost persons becomes more exact when we focus on behaviors of specific groups like “gatherers.” Besides mushrooms, people gather berries, rocks, wood, Christmas trees, piñon nuts, ferns for floral arrangements, and other things. There are aspects of our behavior as mushroomers that complicate our rescue if lost. Koester says that compared to other groups in the gatherer category “Mushroom pickers may not fare as well under long term survival conditions.”

Here are some reasons why this statement is likely true.

• We tend to keep our destinations secret: We rarely tell anyone exactly where we are going.

• We tend not to be on trails, which would at least give us a 50/50 chance of going the right direction and getting out.

• We seldom have a mental picture of the general area.

• We spend all our time looking down.

• We walk in circles.

• 83 percent of us go out alone.

• We never plan to be out very long and tend not to bring extra clothes and emergency supplies.

• We have successfully navigated in and out of the woods before, so we believe this time will be no different.

• 81 percent of us who become lost, do so because of poor or missing navigational skills.

Recommended Steps

So, knowing all the above, there are some recommended steps you can take, which would greatly reduce the risk of becoming lost and, if already lost, would greatly decrease the chances of tragedy. These recommendations fall into two groups: (1) things you can do before you go out and (2) things you can do when already out. Much of this will seem like common sense, but sometimes common sense is a rare commodity in the woods. The following are recommended steps to take before going out.

• Check the weather forecast.

• Assemble the appropriate gear, perhaps in a backpack (all weather clothing and gear, 10 essentials, navigational gear, first aid, whistle, etc.).

• Learn to use your navigational gear.

• Charge your phone and/or take an extra battery or solar charger.

• Line up a hunting buddy.

• Take walkie talkies.

• Know how to send text messages.

• Consider carrying an EPRB (Emergency Personal Rescue Beacon).

• Take spare batteries for your devices (GPS, walkie talkies, etc.).

• Tell someone where you are going and when you intend to be back. There are a few smart phone applications into which you program your contacts and your planned return time. When you return you must call up the application and tell it you have returned otherwise it calls your contacts and tells them you have not returned. (I have not tested these.)

Finally, there are recommended strategies for once you are out in the woods, both before and after you lose yourself.

• Enter waypoints each time you leave your car or a trail. Label these so you will know what “Waypoint 004” for example, really means. Alternatively, you could write down what Waypoint 004 means. The point is not to rely on your memory.

• Note and write down your compass bearing each time you head into the woods, whether on a trail or not. Again, do not rely on your memory.

• Notice landmarks frequently, especially when you leave the car or trail. When you are moving and stop to notice landmarks, turn around and notice what the way back looks like. Try to walk from one landmark to the next, with the last one always visible. If concerned about your ability to do this, consider loosely tying bits of bright colored surveyor’s tape on your path so that one is visible from the next. Remove them on your way out.

• If you have an altimeter (most GPS units have one), note your starting elevation.

• If you have a map, locate yourself on it before starting to walk.

• Don’t hurry; it’s when most accidents occur.

• Recognize the feeling of panic and when you feel it, make yourself sit down and stay put until relaxed. Do not make decisions when under the influence of panic. Use acronym STOP (stop, think, observe, plan).

• Trust your devices.

• When calm, carefully consider your options and make a plan. The plan that is best for you will not be the same every time or the same as the best one for someone else. For example, if you have no navigation devices and did not note landmarks on the way in, then backtracking, often a good plan, may not be as good a plan as staying put. Conversely, if you told no one where you were going but did note landmarks, then backtracking might be preferable to staying put.

In Summary

So there is no one best plan for every situation. Your best plan will depend on variables such as weather, the gear you have, whether or not anyone else knows where you are, how observant you were going into the woods, and especially your ability to stay calm. Panic is by far the biggest killer in wilderness emergencies. Preventing emergencies is much easier and preferable to managing them.

Reference; Koester, Robert J., Lost Person Behavior; a Search and Rescue Guide for Where to Look for Land, Air, and Water. dbS Productions, PO Box 94, Charlottesville, VA 22901 (www.dbs-sar.com) 2008. Also available on Amazon.com.

California vs. Italy: a Mini Mushroom Smackdown

By Brother Mark Folger (repost from November 2014) It’s mushroom season in Italy. There are roadside mushroom stands popping wherever forests meet little country towns. The locals are quite proud of their fungal treasures, and they know them very well; they’ve been picking them for millennia. You’d think you were in California; most of our best edibles are here. They also have some great edibles that we usually only find back east, such as Hen of the Woods. There are, however, no Hericium, at least none that I know of. Pow. Take that, Italy.

Sadly, I didn’t get to pick the mushrooms you see below myself. I bought them at a roadside stand and finally did a long-awaited taste-off. After the simplest sauté possible –– just butter and salt –– I noticed that there were some curious differences between the mushrooms of the New and Old Worlds, even within the same species.

Top: “Galletto” Cantharellus cibarius: The color of our Bay Area chanterelles was there, and the fresh scent was slightly suggestive of Juicy Fruit gum. But unlike our pristine California specimens, these guys had some burrowing Italian vermin to deal with during slicing. the fruity scent completely disappeared during cooking. They were meaty and rich, texturally the same as California’s, but I’d say they were missing that hint of caramel and maple many of us have noticed at home. Still very good though.

Left: “Trombetta dei morti” Craterellus cornucopioides: Looks the same as ours, but there are no redwood-madrone stands here. What Italy does have are forests of chestnut trees; everybody eats chestnuts here, there’s more ground fall than you can deal with. Wild boars get fat on them. Mushrooms of all kinds seem to love growing in chestnut duff with a sprinkling of oak. These Craterellus were not as fragrant as ours at home, but they cooked up jet black with a rustic, pleasantly earthy favor. I didn’t have the sense I was eating truffles, but these turned out tender and delicate with none of that woody texture we sometimes have to put up with. Perfect for a risotto.

Bottom: “Porcino” Boletus edulis - I have to say it. Better than ours. I have sometimes noticed a slight bitterness in our Spring Kings that is not always appetizing. These Italian boletes had none of that. Just rich and lightly nutty. The buttons were slightly crunchy. Not too much vermin either, but there was a slight infiltration of grit that was tracked in, I think, by what little vermin there were. Our ancestral American chestnut forests are long gone due to the blight, but I wonder how the Boletus edulus growing there might have compared.

Right: “Ferlengo” Pleurotus eryngii, variety ferulae (or just Pleurotus ferulae). This mushroom usually grows in association with a special plant: the genus Ferula, or the Giant Fennel. Some giant fennels around the Mediterranean and Middle East are reputed to have various medicinal properties, particularly libido enhancement. Ferlengo mushrooms are said to share the same medicinal properties as their host, and sometimes mushroom and plant are eaten in the same meal. The mythical spice silphium was actually a giant fennel from Libya. Apparently it was confined there because it couldn’t be cultivated, but had such a wonderful favor that the ancient Greeks and Romans picked it to extinction –– the last stalk was said to have been presented to the emperor Nero. One wonders if it had its own ferlengo. Unlike silphium, ferlengo can be cultivated. In the U.S. it has chubby stems and small caps. You’ve seen it in the supermarket with fancy names like “king oyster” or “royal trumpet.” These wild ones were quite rich and juicy, not unlike oyster mushrooms, but with a more tender texture. I’m a fan, but I wouldn’t pick it unless I found it growing with giant fennel. It’s too easy for a beginner to confuse with a toxic lookalike. Happy hunting, y’all.

Culinary Corner

Patricia George (repost from November 2013) I just read an article in the Chron via the New York Times, “Mushroom’s magic vanishes with glut”. Sad for the commercial pickers but good for us mushrooming hobbyists. The mushroom featured is matsutake, Tricholoma magnivelare. Highly prized by Japanese, especially, this mushroom has brought obscenely high prices in the past making commercial foraging a good income but this year is so prevalent that pickers are getting only about $5.00 a pound where they once could get $600.00 a pound when at their peak. Now, other countries are providing matsutake, the Japanese and other world economies have worsened, and the Oregon featured market has greatly declined, a glut or not.

The Pacific Northwest has had a lot of rain; that probably explains the glut of mushrooms, but heavy rainfall doesn’t always produce great fruitings. Hopefully, we will see matsutake this mushroom season further north in California at our MSSF Mendocino foray, at Salt Point and maybe even in the East Bay hills. They will probably appear at lower than usual prices at local greengrocers if you can’t find any yourself.

Matsutake; Tricholoma magnivelare

Photo: Michael Wood

The mushroom, once described by David Arora as having a “unique, spicy odor-a provocative compromise between “red hots” and dirty socks”, is delicious but deserves to be prepared in ways that are different than how we usually prepare wild mushrooms. Don’t sauté them in butter or olive oil. Their flavor is better appreciated in simple recipes featuring their unique flavor. No, they don’t really taste like “red hots” or dirty socks; they lend a lovely spicy aroma and a subtle but rich and pleasing taste. Use them to perfume your pot of rice, adding a few slices at the beginning and letting them cook with the rice. Put them in your favorite sukiyaki recipe. Or add them to udon soup.

I love easy recipes. Here’s one for:

Chicken and Matsutake in Parchment

Ingredients:

1 bunch of green onions, trimmed

¼ cup sake

1 tablespoon of soy sauce

2 boneless, skinless chicken breasts, about 8 oz. ea. (It may be the world’s most boring meat but it really gets gussied-up with matsutake!)

2 ounces matsutake, thinly sliced

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees. Cut two pieces of parchment paper about 18 inches long. Fold each in half lengthwise and trim the paper into an oversized heart shape.

Cut the green onions in 3-inch lengths and cut the pieces lengthwise into julienne. Put them in a little bowl and drizzle them with the sake and soy sauce. Toss and let sit for 5 to 10 minutes.

Lift the onions from the bowl letting the liquid drip back into it. Put the onions on one of half of the parchment heart, just in from the folded edge then set a chicken breast over the onions. Drizzle half the liquid over the chicken breast and lay the matsutake slices on top. Repeat with the other parchment heart and onions and chicken, liquid, and mushroom slices.

For each packet, fold the other half of the parchment heart over the chicken breast. Starting at the top of the heart at the folded edge, begin making short folds that overlap a bit, working all around the cut open edges to fully seal them. If your edge doesn’t seem well sealed and you have enough paper, you can go back around and do the same again.

Set the packets on a baking sheet and bake for 18 minutes. Carefully transfer the packets to individual plates and snip open the top. Be careful to avoid the first blast of steam but step back and inhale the divine aroma.

Chanterelles are a favorite November treasure in the woods also, a lot less elusive than matsutake. We’ll find them, I’m quite sure, at our MSSF Mendocino foray. I had the most delicious, unforgettable chanterelle and pappardelle pasta with pecorino cheese creation at a restaurant in Soho when I visited a friend in Manhattan recently. Try sautéing your chanterelles in unsalted butter, salt and black pepper and adding shallots, thyme and crushed red pepper after the mushrooms have gotten golden in color. Cook for about 5 minutes, stirring. Add a bit of sherry vinegar and deglaze the pan. Add chicken stock and simmer until a bit thickened.

Cook fazzoletti (handkerchief pasta) until al dente, drain and add to the mushroom sauce, add some butter and sauté gently for a couple of minutes. Plate it and sprinkle with chives and toasted hazelnuts.

Here’s my favorite quote about cooking. It’s from Madame Jehane Benoit, Canadian cook and author: “I feel a recipe is only a theme which an intelligent cook can play each time with a variation.”

By the way, you can get help figuring out how much you need of ingredients when you cook for a big group. Just go to allrecipes.com, check a recipe that is somewhat like your own and change the servings number to yours. The site will calculate how much you need, and you can tweak it to your own recipe.

Maybe see you at the MSSF Mendocino Foray or other woodsy spots, or at dinner. –Pat

MSSF Culinary Group November Dinner

Monday, November 6th, 2023 (6:00pm)

Hall of Flowers (County Fair Building)

9th Avenue & Lincoln Way; Golden Gate Park; San Francisco

(Register in the "members only" area of www.mssf.org )

The MSSF Culinary Group's November 2023 Dinner event will be will be "A Fungal Thanksgiving", main dish; a candy cap glazed salmon. Head Chef: Heather Lunan.

Bring an appetizer to share. We will dine at the Hall of Flowers (County Fair Building; 9th Avenue & Lincoln Way) in Golden Gate Park. Please arrive between 5:30pm and 5:45pm to help set up tables and chairs.

The guest chef at the last general meeting was Stephanie Wright. She made stuffed mushrooms and a delicious spice cake.

As usual, BYOB. You will also need to bring your own tablecloth, glassware, place settings, napkins, etc. We will conduct a short business meeting (bring your fun fungal ideas!) at 6pm; potluck follows immediately. Everyone will be asked to help break down and clean up at the end of the evening ...since we need to be out of the building by 9:30 pm.

Covid protocols: In light of SF's current Covid surge, please do not attend this event if you are not feeling well, if you have any cold or flu symptoms, any symptoms of Covid-19, or if you are not fully vaccinated against Covid-19. (Masking is optional and masks will be provided for those who wish to use them when not actually seated and eating.) Thank you very much for your cooperation!

Registration is required to attend, fee is $20 for members, $25 for guests, and children are half price. Only MSSF members whose dues are current may join the Culinary Group, however...so please make sure your MSSF dues are paid up before registering for this dinner. Questions? Problems registering? Call Paul 415-515-1593 or Maria 415-305-3316 (Culinary Group co-Chairs).

MSSF Mendocino Woodlands Camp

David Gardella Only a Few More Days Until….

MSSF MENDOCINO WOODLANDS CAMP

“A Return to Food - Forays - Fun”

November 10-12, 2023

Deep in the Mendocino Woodlands, MSSF members, friends, and family, gather once again for our annual north coast fungal rite of autumn. This weekend-long spectacular mycological event includes great mushroom themed dinners, guided forays, fun informative presentations, and plenty of mushrooms!

Thanks to all of you MSSF members who are signed up for this year’s triumphant fungal return to the Woodlands! Stay tuned for a camp summary article in the December Mycena News. And for those of you that wanted to attend Mendo Camp but couldn’t this year, mark your calendars for the next Mendo Camp which will be held November 8th – 10th , 2024.

2023 Friday evening presenter will be: Stephanie Jarvis

2023 Saturday evening presenter will be: Maria Morrow

Additional mushroom workshops and talks by Elissa Callen, Gayle Still, Phil Minnick, Stephanie Manara, and Else Vellinga, Mendo Camp Mycologist.

2023 Mendo Camp Foray Leaders & Co-Leaders:

Norm Andersen, JR Blair, Jenna Hinshaw, Stephanie Jarvis, Ken Litchfield, Stephanie Manara, Maria Morrow, Pascal Pelous, Maria Pham, Brennan Wenck

CANCELATION/REFUND POLICY: A $20 processing fee will be applied to any cancelation requests made prior to Friday 11/3/23. Any cancelation requests made after 12:00am Friday 11/3 will receive a refund of 50% of the ticket price. The lesser refund amount available for cancelations made within one week of camp due to the fact that exact attendee numbers for our catering reservations and Woodlands fees leading up to camp will need to be confirmed at that point.

For more information about Mendo Camp, please visit in the Mendo Camp Info Page on the MSSF website or the Groups.io Mendo Camp Foray page

For registration questions, please e-mail Stephanie Wright at: mendoregistrar@mssf.org or call (510)-388-5009. For general camp questions, please email David Gardella at: mendodirector@mssf.org or call (602)-617-0150. The above e-mail addresses can also be used if you need help with the online reservation process.

Additional information about the Mendocino Woodlands Camp can be found at: www.MendocinoWoodlands.org (FAQS, MAPS & DIRECTIONS). |